|

‘What reorientation is needed in legal scholarship, advocacy, and policy making on the future of borders and migration governance, if the neocolonialism of borders and the racial injustices are a fundamentally corporate affair?’ asked Tendayi Achiume in the inaugural Alfred Dubs Lecture titled Race, Corporate ‘Sovereigns’ and Corporate Borders. Brutal deaths of migrants trying to cross borders to Europe have in the past couple of decades become daily occurrences. Why is it that citizens of some countries need visas to enter the Schengen zone and others do not? Why do citizens of African countries with ‘UK descent’ (read: White) have a different visa regime than their Black co-citizens? International law is not neutral, Tendayi Achiume demonstrated. When analysed within the persistent colonial structures of race, geopolitics, and corporate empire, borders emerge as a racial imperial technology and a means of extracting value from bodies and regions. Transnational corporations benefit from the border- industrial complex, whose foundations were laid during European colonialism. The electric fences built on the border between Zimbabwe and South Africa by the apartheid regime are today’s sites of migrant deaths. Those who succeed in crossing become exploited, rightless workers, producing goods that are then sent to Europe, crossing multiple borders without impediment. At the US-Mexico border, Mexicans ‘donate’ their plasma to medical corporations in exchange for a ten-year US visa. The plasma, the blood spilled by barbed wires, knives, and bullets, and the black and brown bodies washed up on European shores are the substances in which the corporate and corporal characteristics of borders meet, flow into one another, and mix.

|

|

In his Theses on the Philosophy of History, Walter Benjamin asserts that it is in the narratives of the past that the oppressed and dispossessed may find their revolutionary potential, which does not surrender to dominant visions of progress. However, recovering traces, objects, and knowledge from the ruins of cultural destruction requires continuous effort, as Fatima El-Tayeb noted in her lecture on Transformative Archives and Queer Spacetime. Analysing her engagement with the ‘Intersectional Black European Studies Project’ through a decolonial queer of colour perspective, Fatima illustrated that recovering the histories of Black Europeans and their decolonial struggles fundamentally challenges the modern European ordering of time and space. Yet, archives as a form of knowledge inherently carry the risk of reproducing hegemonic structures of belonging and silencing some narratives while upholding others. Therefore, instead of producing a homogeneous counter-account, the project embraces heterogeneity of stories, ambiguity, and openness.

|

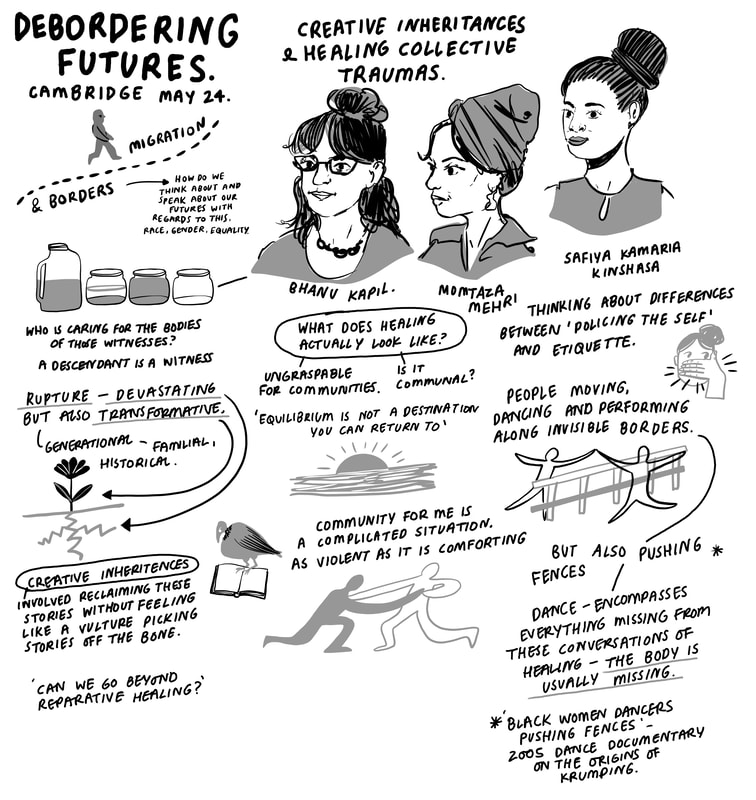

The possibilities of queering ethnicity, and radical black worlding were further explored at the panel Creative Inheritances and Healing Collective Traumas, presenting ancestral artistic worldbuilding with poets Bhanu Kapil, Momtaza Mehri, and Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa, co-moderated by Dita N Love and Lina Fadel. Lina spoke in defence of fragments as a creative method across community and academia, where the collaboration between the Debordering Futures event and the other side of hope is located. Bhanu’s talk was a critical poem and anti/performance dialoging diasporic form which she described as ‘an attempt to remember something that nothing in your environment prompts [...] to incubate fragments.’

|

Bhanu’s performance radically subverted vicious racist attacks she had witnessed in her neighbourhood during childhood, when racists stopped by the houses of Brown and Black people to empty the bottles of milk in front of their doors and replace the milk with urine in an act of racial hatred. Bhanu’s work unsettled acts of brutality and showed that racialised colonial trauma demands a practise of communal somatic tending beyond repair. Momtaza Mehri read poetry from her award-winning collection Bad Diaspora Poems, and interrogated ‘intergenerational familial ruptures’ as ‘reinvention.’ Momtaza differentiated between a ‘conservatively narcissistic poet’ exploiting people’s experiences like ‘a vulture picking off other peoples’ stories to the bone’; and a ‘radically narcissistic poet’ who becomes ‘responsible with pain’; aware when ‘we are too shrunken for reciprocity’; and accountable with how ‘we stand as evidence of a murderous legacy’. Disrupting superficial ‘healing’, Momtaza elucidated how community also harbours un/seen ‘catastrophe in [its] mundanity’. She noted that ‘kinship is more than kindling of lullabies’ invoking the legacy of South African singer and activist Zenzile Miriam Makeba, known as Mama Africa. On the topic of creative inheritances, Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa embodied a new ethnographic method she is developing in relation to ‘ancestral improvisational dance techniques as a form of non-verbal communication’, common in Barbadian dance vernacular. She also read from her debut poetry collection Cane, Corn & Gully (2022), where she used sparse Anglo-colonial descriptions of enslaved women dancing as a foundation to unearth nuanced narratives of the lives of Black Barbadian women and their descendants. Safiya critiqued literary exclusions, and traced lineages of African and Afro-diasporic dance from the Caribbean to the US.

|