|

Diasporic knowledge and self-knowledge are rooted in past inheritance and in anticipated futures. Articulating these amidst violent attempts of assimilation, silencing, and extermination becomes a matter of survival. During the ongoing genocide in Gaza, committed by the Isreali state and supported by the UK among others, the panel titled (De)bordering Palestine, moderated by Kareem Estefan, was an act against the historical oblivion imposed by dominant narratives that present the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians as a response to the violent Hamas attacks. A look into the history of Palestine shows us that the Zionist settler-colonial occupation from the outset entailed persistent and recurring acts of extermination and displacement, and, importantly, that the Palestinian people have always resisted them. In their separate talks, Akram Salhab and Riya Al-Sanah took us into the history of (de)bordering Palestine. We learned about the ways in which the borders cut people from their ancestral land and brutally severed ties to their traditions, as well as the ways in which the Palestinian people self-organised for struggles against borders and boundaries on many fronts and in different historical periods. What emerges from ‘debordering history’ is a continuity of practices of resistance against annihilation.

|

|

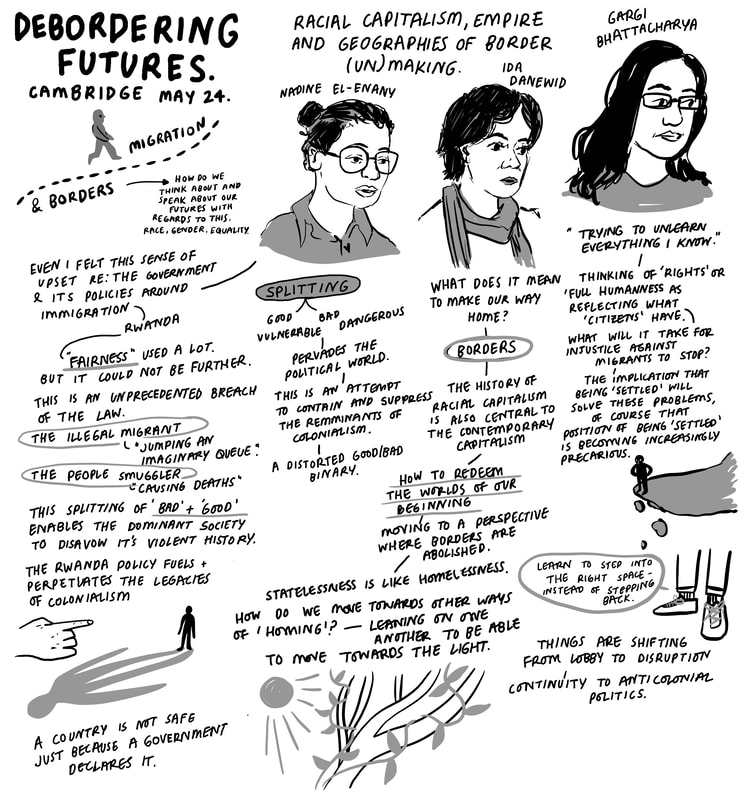

A look into the histories of the oppressed and struggling can open up new perspectives on the systematic violence in the present, perspectives that can generate decolonial knowledge and fuel struggles for a different future. In the session Geographies of Racial Capitalism and Border (Un)making, Nadine El-Enany began by exploring the UK’s Rwanda Policy, which proposed sending asylum- seekers to Rwanda for application processing. She highlighted how the dominant discourse presented this cruel policy as fair and morally righteous, projecting the idea of ‘the illegal immigrant’ and ‘the smuggler’ as bad actors that need to be removed to purify society. This policy also depicted Rwanda as a hellish, irredeemable place to terrorise migrants, reinforcing the false colonial binary of the civilised versus the barbarous. Ida Danewid explored how border abolition could draw from the history of marronage. Marronage refers to the practice of enslaved Africans escaping plantations to form independent communities, or maroon societies, in remote areas. As Ida noted, these communities were not just escapes from oppression but also processes of creating livable spaces, or ‘homing.’ Inspired by these maroon communities, the question arises: how can we reimagine place and home-making as forms of freedom outside the nation-state? Gargi Bhattacharyya noted that extending citizen-like status to all cannot be the marker of freedom or the ultimate political horizon, as citizenship itself is an uneven and precarious fiction. This sort of advocacy assumes an audience of settled people who only need to be convinced of the rights of the undocumented, restricting us to a politics of lobbying that has had little impact so far.

|