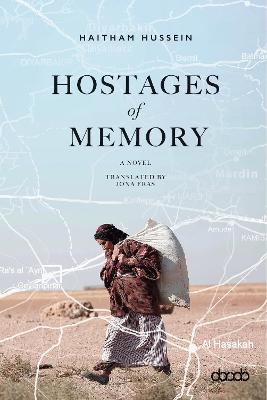

The new dimension of fragmented Kurdish identity revisited in a Haitham Hussein’s novel, Hostages of Memory

The doubted loyalty and questioned patriotism in the Kurdish-populated Mardin province in Turkey, which is less different from what their counterpart face in Al-Hasakah province in Syria are some of the detailed, well-crafted accounts shared at a personal level by Haitham Hussein in his fast-paced novel, Hostages of Memory.

In the Hostages, which was originally written in Arabic and recently translated into English, the Syrian Kurdish novelist Haitham Hussein deals with the fragmentation of the Kurdish identity, and focuses on the Kurds of Syria and Turkey, where on both sides of the border – in Mardin province (Turkey) and Al-Hasakah province (Syria) this ethnicity finds itself having its loyalty and patriotism doubted and questioned by the authorities.

It takes a reading of the Hostages to share, just like a witness, of the experience of Hussein: telling the aspects of the effects left by the borders between Syria and Turkey with its various dimensions, political, religious, intellectual, and social, on the people of those areas, and how the geographical division cast a shadow on the Kurds historically, as well as how the minefields on the borders caused disasters for those who tried to cross it.

The novel deals with the impact of global alliances and major events on the Kurds and their identity, especially the case of individuals who seem marginalized and far from caring, while bearing the burdens of its consequences.

The novel takes place in the sixties, and begins with the period of separation between Egypt and Syria where positions contradict between a supporter of President Gamal Abdel Nasser and an opponent who criticizes him.

The main character in Hostages of Memory is Khatoune, an older woman going by the Kurdish coinage of Khatoune Giay, meaning that she descends from mountainous area. She bears the traits of a mountainous woman: stubborn, patient and mysterious. She travelled and emigrated a lot, until she settled in the city of ‘Amouda’ with her two children, Ahmed and Ali, who were known as Ahme and Alo. She moves them to protect them from death, and to keep them away from the values of vengeance and revenge. Khatoune hides her story, for nearly half a century, and tries to overcome the pain of the past, but while she is injured and bleeding at the border, she reveals to her grandson the secrets of the family and the mysteries of the journey they all lived through.

The novel’s protagonist avoids answering any questions about her private life, her past, or where she came from. She works as a midwife for the women of the town. She was described as hard-hearted during childbirth because she did not pay attention to their cries while she was doing her work, as if she had not given birth to her two children and had not experienced anything from the pangas of childbirth.

Ahme was more religious than Alo, who used to justify his actions as part of trade saying that the Messenger Mohammed, with his majesty, was a merchant. Alo married a girl and had a son whose name was Hawar.

After some painful events, Ahme flees to Turkey, to settle in the village of Qarashiki, one of the villages of Mardin, where he married the daughter of an imam. His brother Alo stays with his family, but is isolated for a period to return to his work as a porter, and soon he dies after falling from the wheat sacks.

The grandmother, Khatoune, learns of her son’s whereabouts, Ahme. She travels to him with Hawar to persuade him to return home! But she fails in her mission. Then she leaves to return home, crossing the Turkish-Syrian border again. However, she was hit by the bullets from the border guards who wanted to warn her, but he did not understand their Turkish language, so they fired the warning bullet, killing her.

Khatoune reveals to her grandson, Hawar, the secret she has carried throughout her life. And here is the novel’s plot tucks to climax: the great-grandfather participated in the Korean War and legends were woven around his wealth, and he became coveted by the bandits who killed him, stole his wealth, and took revenge on his family.

Alo’s wife lost her hearing after she became a victim of her father’s mistrust. Her father heard in the market that the girls used the excuse of sweeping in front of the house door for their lovers. And when the daughter was sweeping in front of the house, she was surprised by her father’s return early cursing and hitting her, then he slapped her and hit her head on the wall.

The female characters appear in multiple images in the novel. They seem strong at times and the oppressed at other times. The writer describes that by saying: ‘The women’s daily toil was surely a form of resistance, and their ultimate cause; and their first concern was to educate their children so they wouldn’t repeat the mistakes of their parents, and their ancestors. The advice they gave their children, along with their husbands, was spontaneous and sincere: “We don’t want you to live a life like ours.”’

The teacher’s character comes as a revolutionary equaliser against the reality of ignorance, backwardness, and tyranny. This personality quickly disappears, but it is influential in the course of the characters and their future, as he named Alo’ son Hawar, which means ‘The Scream.’ And, he said ‘I hope for him to be a true embodiment of his name,’ said the teacher adding; ‘a cry of rejection for all that his ancestors have suffered! It will light the fire of revolution against those who turned his family into vagabonds and beggars, and made of him a refugee in every place he will run to.’

This novel is against injustice, oppression, and domination in all its forms and manifestations. Places also have their presence in the novel. There are hotbeds of poverty and humiliation of need. There are smuggling routes on the Turkish-Syrian border, often with difficulties and dangers. The barbed wire that stand as a barrier between members of the same family and the separation of loved ones.

Not all places are sad. In Hawar’s trip to the border villages on the Turkish side, there are aesthetics, pleasures, and delightful stories. There is a narration of the history of the places, the languages of their owners, and the folk stories associated with them, where history overlaps with memory, for example, the history of Mardin and the origin of the naming. The demographic change of places and succession of different religions such as Christians, Jews, Muslims, and ethnicities like Arabs, Kurds, Syriacs, Turks and others. Those conversations that young people hear in the circles of adults so their memory stores these stories without awareness of recording or memorisation. Hawar, whose childhood was stolen by circumstances at an early age, talks more about those places and their histories.

There is much historical information in the background of the novel, which is written in a smooth style, as the writer painted by his words an integrated painting of an environment with all its details of daily life and its social and religious traditions.

In the Hostages, which was originally written in Arabic and recently translated into English, the Syrian Kurdish novelist Haitham Hussein deals with the fragmentation of the Kurdish identity, and focuses on the Kurds of Syria and Turkey, where on both sides of the border – in Mardin province (Turkey) and Al-Hasakah province (Syria) this ethnicity finds itself having its loyalty and patriotism doubted and questioned by the authorities.

It takes a reading of the Hostages to share, just like a witness, of the experience of Hussein: telling the aspects of the effects left by the borders between Syria and Turkey with its various dimensions, political, religious, intellectual, and social, on the people of those areas, and how the geographical division cast a shadow on the Kurds historically, as well as how the minefields on the borders caused disasters for those who tried to cross it.

The novel deals with the impact of global alliances and major events on the Kurds and their identity, especially the case of individuals who seem marginalized and far from caring, while bearing the burdens of its consequences.

The novel takes place in the sixties, and begins with the period of separation between Egypt and Syria where positions contradict between a supporter of President Gamal Abdel Nasser and an opponent who criticizes him.

The main character in Hostages of Memory is Khatoune, an older woman going by the Kurdish coinage of Khatoune Giay, meaning that she descends from mountainous area. She bears the traits of a mountainous woman: stubborn, patient and mysterious. She travelled and emigrated a lot, until she settled in the city of ‘Amouda’ with her two children, Ahmed and Ali, who were known as Ahme and Alo. She moves them to protect them from death, and to keep them away from the values of vengeance and revenge. Khatoune hides her story, for nearly half a century, and tries to overcome the pain of the past, but while she is injured and bleeding at the border, she reveals to her grandson the secrets of the family and the mysteries of the journey they all lived through.

The novel’s protagonist avoids answering any questions about her private life, her past, or where she came from. She works as a midwife for the women of the town. She was described as hard-hearted during childbirth because she did not pay attention to their cries while she was doing her work, as if she had not given birth to her two children and had not experienced anything from the pangas of childbirth.

Ahme was more religious than Alo, who used to justify his actions as part of trade saying that the Messenger Mohammed, with his majesty, was a merchant. Alo married a girl and had a son whose name was Hawar.

After some painful events, Ahme flees to Turkey, to settle in the village of Qarashiki, one of the villages of Mardin, where he married the daughter of an imam. His brother Alo stays with his family, but is isolated for a period to return to his work as a porter, and soon he dies after falling from the wheat sacks.

The grandmother, Khatoune, learns of her son’s whereabouts, Ahme. She travels to him with Hawar to persuade him to return home! But she fails in her mission. Then she leaves to return home, crossing the Turkish-Syrian border again. However, she was hit by the bullets from the border guards who wanted to warn her, but he did not understand their Turkish language, so they fired the warning bullet, killing her.

Khatoune reveals to her grandson, Hawar, the secret she has carried throughout her life. And here is the novel’s plot tucks to climax: the great-grandfather participated in the Korean War and legends were woven around his wealth, and he became coveted by the bandits who killed him, stole his wealth, and took revenge on his family.

Alo’s wife lost her hearing after she became a victim of her father’s mistrust. Her father heard in the market that the girls used the excuse of sweeping in front of the house door for their lovers. And when the daughter was sweeping in front of the house, she was surprised by her father’s return early cursing and hitting her, then he slapped her and hit her head on the wall.

The female characters appear in multiple images in the novel. They seem strong at times and the oppressed at other times. The writer describes that by saying: ‘The women’s daily toil was surely a form of resistance, and their ultimate cause; and their first concern was to educate their children so they wouldn’t repeat the mistakes of their parents, and their ancestors. The advice they gave their children, along with their husbands, was spontaneous and sincere: “We don’t want you to live a life like ours.”’

The teacher’s character comes as a revolutionary equaliser against the reality of ignorance, backwardness, and tyranny. This personality quickly disappears, but it is influential in the course of the characters and their future, as he named Alo’ son Hawar, which means ‘The Scream.’ And, he said ‘I hope for him to be a true embodiment of his name,’ said the teacher adding; ‘a cry of rejection for all that his ancestors have suffered! It will light the fire of revolution against those who turned his family into vagabonds and beggars, and made of him a refugee in every place he will run to.’

This novel is against injustice, oppression, and domination in all its forms and manifestations. Places also have their presence in the novel. There are hotbeds of poverty and humiliation of need. There are smuggling routes on the Turkish-Syrian border, often with difficulties and dangers. The barbed wire that stand as a barrier between members of the same family and the separation of loved ones.

Not all places are sad. In Hawar’s trip to the border villages on the Turkish side, there are aesthetics, pleasures, and delightful stories. There is a narration of the history of the places, the languages of their owners, and the folk stories associated with them, where history overlaps with memory, for example, the history of Mardin and the origin of the naming. The demographic change of places and succession of different religions such as Christians, Jews, Muslims, and ethnicities like Arabs, Kurds, Syriacs, Turks and others. Those conversations that young people hear in the circles of adults so their memory stores these stories without awareness of recording or memorisation. Hawar, whose childhood was stolen by circumstances at an early age, talks more about those places and their histories.

There is much historical information in the background of the novel, which is written in a smooth style, as the writer painted by his words an integrated painting of an environment with all its details of daily life and its social and religious traditions.

Matovu Abdallah Twaha, 50, is a trained Ugandan journalist who has previously written for the Ugandan dailies: The Daily Monitor and The Observer (2000) before serving as an Information Officer for Kalangala District Local Government (2001-2007). He then joined The Gulf Today, a daily in the United Arab Emirates (2007-2018). He is now a freelance writer and an entrepreneur dealing in coffee industry in Uganda.